If someone says that he can increase the gross profit by just expanding manufacturing without selling more products, would you believe him?

He certainly sounds like a hustler. But before we jump into the conclusion, let’s take a deeper look at what the problem really is here.

What are included in the manufacturing cost?

Manufacturing cost includes raw materials, direct labor and manufacturing expenses. The first two are pretty easy to understand. Manufacturing expenses include water and electricity expenses in the workshops, and the depreciation of the plant and equipment.

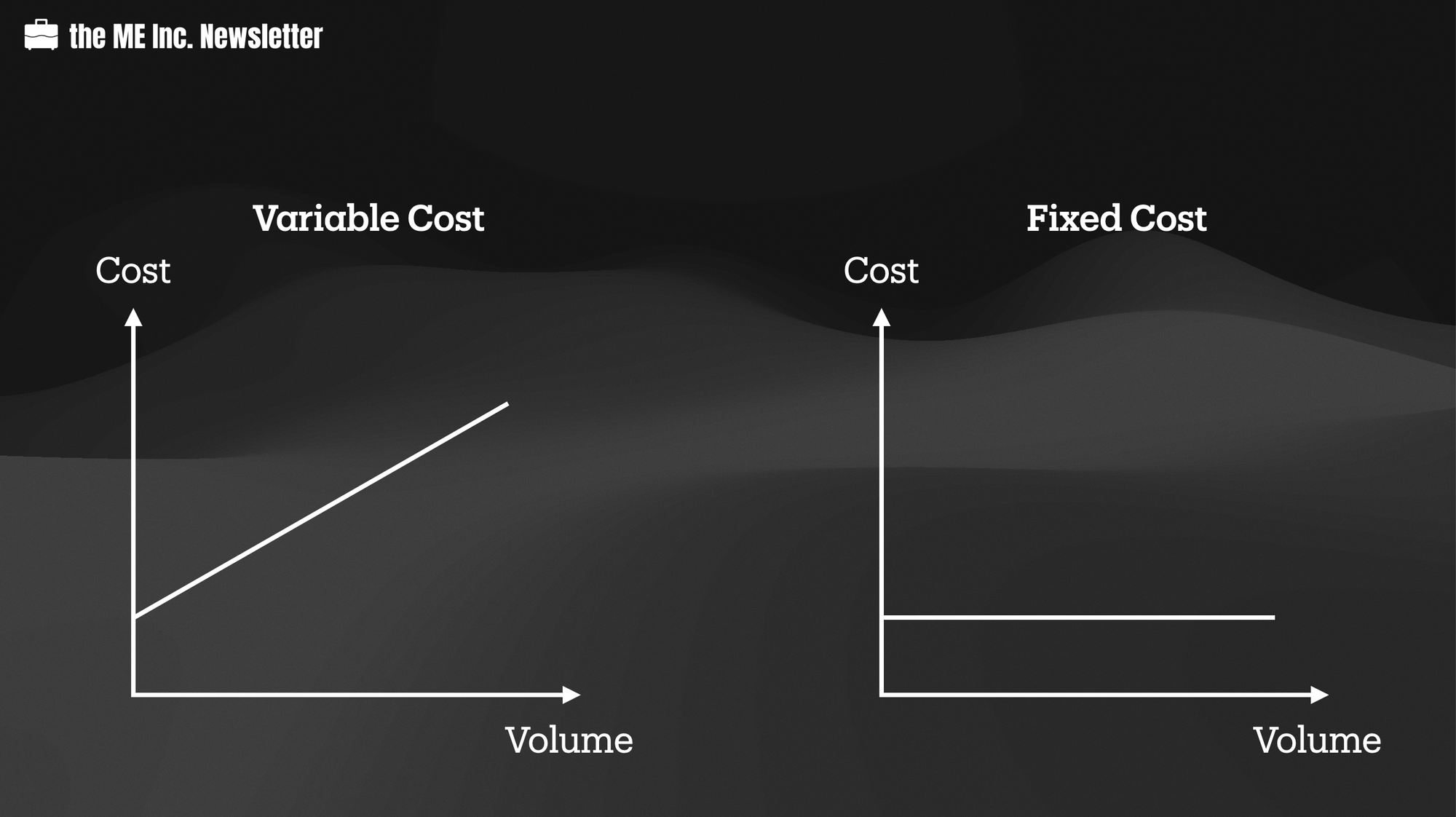

Manufacturing cost can be generally divided into two categories: variable cost and fixed cost.

What is variable cost

Variable cost refers to costs that increase with production volume. In other words, to produce one more product, one more unit of cost occurs.

Obviously, raw materials belong to variable cost, because to produce one more product, we must invest one more unit of raw material.

What is fixed cost

Fixed cost refers to costs that stay the same no matter how many products are produced, to some extent.

It’s easy to find out that depreciation of plant and equipment belongs to fixed cost. No matter how many products are produced,

the expenses for the plant and equipment are always the same, and unless we produce significantly more products, they will not change as our plant produces more units of goods.

Direct labor

So we may say raw materials cost belongs to variable cost, while depreciation belongs to fixed cost. What kind of cost does direct labor belong to?

Well, it depends on how our company pays employees. If a fixed wage is paid regardless of how many units of goods are produced by a worker, direct labor is a fixed cost; if wage is paid per number of units produced, direct labor is a variable cost.

In practice, it is often partially fixed and partially variable.

The importance of dividing manufacturing costs into two groups

Dividing manufacturing costs into separate groups can have fundamental impact on the decision making of our company.

For example, suppose our company produces Stanley cups with a unit variable cost of 60 dollars. We further allocate 40 dollars of fixed cost to each cup. The average total cost per unit is then 100 dollars.

If a potential client places an order for 80 dollars per cup to our company, shall we accept the order?

From the surface, and from the perspective of costs, we should reject the offer because the average cost per cup is higher than the offer. We will lose 20 dollars each cup for the order. However, our alternative of declining the offer is actually losing 40 dollars:

since the fixed costs will always be there, regardless of our production status, every minute we are not producing anything is a minute of losing fixed cost. Even if my output is 0, the total fixed cost is still the same.

From this analysis, it might appears to you that accepting the order would result in a reduction of 20 dollars loss per unit (from -40 to -20). So obviously we should accept the order.

Form the above example we can conclude that it is important to differentiate variable cost from fixed cost. Now let’s look at another example.

Is higher gross profit always a good thing?

Our company produced 1000 products this year. Let’s assume this product is high-tech and high value, and it costs us 10,000 dollars of variable cost per unit, resulting in a total of 10 million dollars of variable cost. Additionally, we’ve also invested 10 million dollars of fixed cost, so our total manufacturing cost is 20 million dollars. We got really lucky and sold all 1000 pieces.

Now, let’s analyze what happened here on our financial statements.

Before we sold any product and after we manufactured all products, the 1000 units were recorded under inventory with a value of 20 million dollars, which is the cost incurred for producing the products. When the products were sold, the 20 million dollar worth of inventory got transferred from inventory (Balance Sheet) to cost of goods sold(Income Statement).

In the second year, we’ve decided to double down in this market. We predict that the market will keep growing and there will be even more demand, so we decide to produce 2000 units in the second year.

Our variable costs will increase to 20 million dollars this year as a result. Our fixed costs, on the other hand, will stay the same. Therefore, our total manufacturing costs have become 30 million dollars.

However, we’ve unfortunately predicted the market trend incorrectly, and have failed to sell the 2000 units of products. Instead, sales this year stay the same as last year at 1000 units. The other 1000 units of products stay as inventory in our warehouse.

Let’s do some analysis here. The 30 million manufacturing cost is originally recorded in inventory. At the time of selling the 1000 units, this portion of inventory is transferred from inventory to cost of goods sold. Because we’ve produced 2000 units and only sold 1000, exactly 50% of inventory will be transferred into cost of goods sold, which is 15 million dollars. And because our sales are still the same at 1000 units, assuming our unit price stays the same, our gross profit actually increases because of the lower cost of goods sold! To be exact, 5 million dollars more!

This result can be baffling to many. If we produce more products but fail to sell more, our gross profit is indeed increased. But any person with some level of common sense will know having too much inventory is bad, not good, for the company.

The explanation

By reading this post, you will be able to understand the reason, which is that because the fixed costs stay the same in both years, the per unit fixed cost got reduced with the increase of manufactured products. And because only 50% of products are sold, only that portion of fixed costs got transferred to cost of goods sold. The other 50% stays as inventory, until they get sold in the future. So even if our revenue stays the same, producing more units of products can actually increase our gross profit.

By now you might have found a problem: normally we think that our firm is more profitable if the gross profit is higher. However

the firm in the above example predicts the market trend incorrectly in the second year, and manufactures too many products, resulting in over-production. If you are asked to judge how the firm’s performance is in the second year, I am sure that you would say it is poor. However, its gross profit is indeed higher.

The conclusion is that we cannot simply take an increase in gross profit as sign of better performance. Growth in gross profit should be interpreted together with the value of finished goods inventory. If gross profit and finished goods increase simultaneously, the increase in gross profit does not necessarily mean a better performance, and we should take it with a grain of salt.

For the same reason, if gross profit and finished goods decrease simultaneously, it could mean that the company is selling lots of finished goods from the inventory, which is almost always a good thing.

@import url(“https://assets.mlcdn.com/fonts.css?version=1714030″); /* LOADER */ .ml-form-embedSubmitLoad { display: inline-block; width: 20px; height: 20px; } .g-recaptcha { transform: scale(1); -webkit-transform: scale(1); transform-origin: 0 0; -webkit-transform-origin: 0 0; height: ; } .sr-only { position: absolute; width: 1px; height: 1px; padding: 0; margin: -1px; overflow: hidden; clip: rect(0,0,0,0); border: 0; } .ml-form-embedSubmitLoad:after { content: ” “; display: block; width: 11px; height: 11px; margin: 1px; border-radius: 50%; border: 4px solid #fff; border-color: #ffffff #ffffff #ffffff transparent; animation: ml-form-embedSubmitLoad 1.2s linear infinite; } @keyframes ml-form-embedSubmitLoad { 0% { transform: rotate(0deg); } 100% { transform: rotate(360deg); } } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer { box-sizing: border-box; display: table; margin: 0 auto; position: static; width: 100% !important; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer h4, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer p, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer span, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer button { text-transform: none !important; letter-spacing: normal !important; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper { background-color: #f6f6f6; border-width: 0px; border-color: transparent; border-radius: 4px; border-style: solid; box-sizing: border-box; display: inline-block !important; margin: 0; padding: 0; position: relative; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper.embedPopup, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper.embedDefault { width: 100%; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper.embedForm { max-width: 100%; width: 100%; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-align-left { text-align: left; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-align-center { text-align: center; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-align-default { display: table-cell !important; vertical-align: middle !important; text-align: center !important; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-align-right { text-align: right; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedHeader img { border-top-left-radius: 4px; border-top-right-radius: 4px; height: auto; margin: 0 auto !important; max-width: 100%; width: 990px; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-successBody { padding: 20px 20px 0 20px; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody.ml-form-embedBodyHorizontal { padding-bottom: 0; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedContent, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-successBody .ml-form-successContent { text-align: left; margin: 0 0 20px 0; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedContent h4, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-successBody .ml-form-successContent h4 { color: #1F5014; font-family: ‘Anton’, sans-serif; font-size: 30px; font-weight: 400; margin: 0 0 10px 0; text-align: center; word-break: break-word; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedContent p, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-successBody .ml-form-successContent p { color: #000000; font-family: ‘Palatino Linotype’, ‘Book Antiqua’, Palatino, serif; font-size: 18px; font-weight: 400; line-height: 24px; margin: 0 0 10px 0; text-align: center; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedContent ul, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedContent ol, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-successBody .ml-form-successContent ul, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-successBody .ml-form-successContent ol { color: #000000; font-family: ‘Palatino Linotype’, ‘Book Antiqua’, Palatino, serif; font-size: 18px; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedContent ol ol, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-successBody .ml-form-successContent ol ol { list-style-type: lower-alpha; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedContent ol ol ol, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-successBody .ml-form-successContent ol ol ol { list-style-type: lower-roman; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedContent p a, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-successBody .ml-form-successContent p a { color: #000000; text-decoration: underline; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-block-form .ml-field-group { text-align: left!important; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-block-form .ml-field-group label { margin-bottom: 5px; color: #333333; font-size: 14px; font-family: ‘Open Sans’, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; font-weight: bold; font-style: normal; text-decoration: none;; display: inline-block; line-height: 20px; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedContent p:last-child, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-successBody .ml-form-successContent p:last-child { margin: 0; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody form { margin: 0; width: 100%; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-formContent, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow { margin: 0 0 20px 0; width: 100%; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow { float: left; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-formContent.horozintalForm { margin: 0; padding: 0 0 20px 0; width: 100%; height: auto; float: left; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow { margin: 0 0 10px 0; width: 100%; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow.ml-last-item { margin: 0; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow.ml-formfieldHorizintal { margin: 0; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow input { background-color: #ffffff !important; color: #333333 !important; border-color: #cccccc; border-radius: 4px !important; border-style: solid !important; border-width: 1px !important; font-family: ‘Lucida Sans Unicode’, ‘Lucida Grande’, sans-serif; font-size: 14px !important; height: auto; line-height: 21px !important; margin-bottom: 0; margin-top: 0; margin-left: 0; margin-right: 0; padding: 10px 10px !important; width: 100% !important; box-sizing: border-box !important; max-width: 100% !important; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow input::-webkit-input-placeholder, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow input::-webkit-input-placeholder { color: #333333; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow input::-moz-placeholder, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow input::-moz-placeholder { color: #333333; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow input:-ms-input-placeholder, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow input:-ms-input-placeholder { color: #333333; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow input:-moz-placeholder, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow input:-moz-placeholder { color: #333333; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow textarea, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow textarea { background-color: #ffffff !important; color: #333333 !important; border-color: #cccccc; border-radius: 4px !important; border-style: solid !important; border-width: 1px !important; font-family: ‘Lucida Sans Unicode’, ‘Lucida Grande’, sans-serif; font-size: 14px !important; height: auto; line-height: 21px !important; margin-bottom: 0; margin-top: 0; padding: 10px 10px !important; width: 100% !important; box-sizing: border-box !important; max-width: 100% !important; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow .custom-radio .custom-control-label::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow .custom-radio .custom-control-label::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow .custom-checkbox .custom-control-label::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow .custom-checkbox .custom-control-label::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedPermissions .ml-form-embedPermissionsOptionsCheckbox .label-description::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-interestGroupsRow .ml-form-interestGroupsRowCheckbox .label-description::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow .label-description::before { border-color: #cccccc!important; background-color: #ffffff!important; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow input.custom-control-input[type=”checkbox”]{ box-sizing: border-box; padding: 0; position: absolute; z-index: -1; opacity: 0; margin-top: 5px; margin-left: -1.5rem; overflow: visible; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow .custom-checkbox .custom-control-label::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow .custom-checkbox .custom-control-label::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedPermissions .ml-form-embedPermissionsOptionsCheckbox .label-description::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-interestGroupsRow .ml-form-interestGroupsRowCheckbox .label-description::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow .label-description::before { border-radius: 4px!important; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow input[type=checkbox]:checked~.label-description::after, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedPermissions .ml-form-embedPermissionsOptionsCheckbox input[type=checkbox]:checked~.label-description::after, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow .custom-checkbox .custom-control-input:checked~.custom-control-label::after, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow .custom-checkbox .custom-control-input:checked~.custom-control-label::after, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-interestGroupsRow .ml-form-interestGroupsRowCheckbox input[type=checkbox]:checked~.label-description::after { background-image: url(“data:image/svg+xml,%3csvg xmlns=’http://www.w3.org/2000/svg’ viewBox=’0 0 8 8’%3e%3cpath fill=’%23fff’ d=’M6.564.75l-3.59 3.612-1.538-1.55L0 4.26 2.974 7.25 8 2.193z’/%3e%3c/svg%3e”); } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow .custom-radio .custom-control-input:checked~.custom-control-label::after, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow .custom-radio .custom-control-input:checked~.custom-control-label::after { background-image: url(“data:image/svg+xml,%3csvg xmlns=’http://www.w3.org/2000/svg’ viewBox=’-4 -4 8 8’%3e%3ccircle r=’3′ fill=’%23fff’/%3e%3c/svg%3e”); } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow .custom-radio .custom-control-input:checked~.custom-control-label::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow .custom-radio .custom-control-input:checked~.custom-control-label::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow .custom-checkbox .custom-control-input:checked~.custom-control-label::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow .custom-checkbox .custom-control-input:checked~.custom-control-label::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedPermissions .ml-form-embedPermissionsOptionsCheckbox input[type=checkbox]:checked~.label-description::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-interestGroupsRow .ml-form-interestGroupsRowCheckbox input[type=checkbox]:checked~.label-description::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow input[type=checkbox]:checked~.label-description::before { border-color: #000000!important; background-color: #000000!important; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow .custom-radio .custom-control-label::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow .custom-radio .custom-control-label::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow .custom-radio .custom-control-label::after, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow .custom-radio .custom-control-label::after, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow .custom-checkbox .custom-control-label::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow .custom-checkbox .custom-control-label::after, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow .custom-checkbox .custom-control-label::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow .custom-checkbox .custom-control-label::after { top: 2px; box-sizing: border-box; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedPermissions .ml-form-embedPermissionsOptionsCheckbox .label-description::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedPermissions .ml-form-embedPermissionsOptionsCheckbox .label-description::after, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow .label-description::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow .label-description::after { top: 0px!important; box-sizing: border-box!important; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow .label-description::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow .label-description::after { top: 0px!important; box-sizing: border-box!important; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-interestGroupsRow .ml-form-interestGroupsRowCheckbox .label-description::after { top: 0px!important; box-sizing: border-box!important; position: absolute; left: -1.5rem; display: block; width: 1rem; height: 1rem; content: “”; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-interestGroupsRow .ml-form-interestGroupsRowCheckbox .label-description::before { top: 0px!important; box-sizing: border-box!important; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .custom-control-label::before { position: absolute; top: 4px; left: -1.5rem; display: block; width: 16px; height: 16px; pointer-events: none; content: “”; background-color: #ffffff; border: #adb5bd solid 1px; border-radius: 50%; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .custom-control-label::after { position: absolute; top: 2px!important; left: -1.5rem; display: block; width: 1rem; height: 1rem; content: “”; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedPermissions .ml-form-embedPermissionsOptionsCheckbox .label-description::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-interestGroupsRow .ml-form-interestGroupsRowCheckbox .label-description::before, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow .label-description::before { position: absolute; top: 4px; left: -1.5rem; display: block; width: 16px; height: 16px; pointer-events: none; content: “”; background-color: #ffffff; border: #adb5bd solid 1px; border-radius: 50%; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedPermissions .ml-form-embedPermissionsOptionsCheckbox .label-description::after { position: absolute; top: 0px!important; left: -1.5rem; display: block; width: 1rem; height: 1rem; content: “”; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow .label-description::after { position: absolute; top: 0px!important; left: -1.5rem; display: block; width: 1rem; height: 1rem; content: “”; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .custom-radio .custom-control-label::after { background: no-repeat 50%/50% 50%; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .custom-checkbox .custom-control-label::after, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedPermissions .ml-form-embedPermissionsOptionsCheckbox .label-description::after, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-interestGroupsRow .ml-form-interestGroupsRowCheckbox .label-description::after, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow .label-description::after { background: no-repeat 50%/50% 50%; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow .custom-control, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow .custom-control { position: relative; display: block; min-height: 1.5rem; padding-left: 1.5rem; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow .custom-radio .custom-control-input, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow .custom-radio .custom-control-input, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow .custom-checkbox .custom-control-input, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow .custom-checkbox .custom-control-input { position: absolute; z-index: -1; opacity: 0; box-sizing: border-box; padding: 0; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow .custom-radio .custom-control-label, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow .custom-radio .custom-control-label, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow .custom-checkbox .custom-control-label, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow .custom-checkbox .custom-control-label { color: #000000; font-size: 12px!important; font-family: ‘Open Sans’, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; line-height: 22px; margin-bottom: 0; position: relative; vertical-align: top; font-style: normal; font-weight: 700; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-fieldRow .custom-select, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow .custom-select { background-color: #ffffff !important; color: #333333 !important; border-color: #cccccc; border-radius: 4px !important; border-style: solid !important; border-width: 1px !important; font-family: ‘Lucida Sans Unicode’, ‘Lucida Grande’, sans-serif; font-size: 14px !important; line-height: 20px !important; margin-bottom: 0; margin-top: 0; padding: 10px 28px 10px 12px !important; width: 100% !important; box-sizing: border-box !important; max-width: 100% !important; height: auto; display: inline-block; vertical-align: middle; background: url(‘https://assets.mlcdn.com/ml/images/default/dropdown.svg’) no-repeat right .75rem center/8px 10px; -webkit-appearance: none; -moz-appearance: none; appearance: none; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow { height: auto; width: 100%; float: left; } .ml-form-formContent.horozintalForm .ml-form-horizontalRow .ml-input-horizontal { width: 70%; float: left; } .ml-form-formContent.horozintalForm .ml-form-horizontalRow .ml-button-horizontal { width: 30%; float: left; } .ml-form-formContent.horozintalForm .ml-form-horizontalRow .ml-button-horizontal.labelsOn { padding-top: 25px; } .ml-form-formContent.horozintalForm .ml-form-horizontalRow .horizontal-fields { box-sizing: border-box; float: left; padding-right: 10px; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow input { background-color: #ffffff; color: #333333; border-color: #cccccc; border-radius: 4px; border-style: solid; border-width: 1px; font-family: ‘Lucida Sans Unicode’, ‘Lucida Grande’, sans-serif; font-size: 14px; line-height: 20px; margin-bottom: 0; margin-top: 0; padding: 10px 10px; width: 100%; box-sizing: border-box; overflow-y: initial; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow button { background-color: #000000 !important; border-color: #000000; border-style: solid; border-width: 1px; border-radius: 4px; box-shadow: none; color: #ffffff !important; cursor: pointer; font-family: ‘Lucida Sans Unicode’, ‘Lucida Grande’, sans-serif; font-size: 14px !important; font-weight: 700; line-height: 20px; margin: 0 !important; padding: 10px !important; width: 100%; height: auto; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-horizontalRow button:hover { background-color: #1F5014 !important; border-color: #1F5014 !important; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow input[type=”checkbox”] { box-sizing: border-box; padding: 0; position: absolute; z-index: -1; opacity: 0; margin-top: 5px; margin-left: -1.5rem; overflow: visible; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow .label-description { color: #000000; display: block; font-family: ‘Open Sans’, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif; font-size: 12px; text-align: left; margin-bottom: 0; position: relative; vertical-align: top; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow label { font-weight: normal; margin: 0; padding: 0; position: relative; display: block; min-height: 24px; padding-left: 24px; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow label a { color: #000000; text-decoration: underline; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow label p { color: #000000 !important; font-family: ‘Open Sans’, Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif !important; font-size: 12px !important; font-weight: normal !important; line-height: 18px !important; padding: 0 !important; margin: 0 5px 0 0 !important; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow label p:last-child { margin: 0; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedSubmit { margin: 0 0 20px 0; float: left; width: 100%; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedSubmit button { background-color: #000000 !important; border: none !important; border-radius: 4px !important; box-shadow: none !important; color: #ffffff !important; cursor: pointer; font-family: ‘Lucida Sans Unicode’, ‘Lucida Grande’, sans-serif !important; font-size: 14px !important; font-weight: 700 !important; line-height: 21px !important; height: auto; padding: 10px !important; width: 100% !important; box-sizing: border-box !important; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedSubmit button.loading { display: none; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-embedSubmit button:hover { background-color: #1F5014 !important; } .ml-subscribe-close { width: 30px; height: 30px; background: url(‘https://assets.mlcdn.com/ml/images/default/modal_close.png’) no-repeat; background-size: 30px; cursor: pointer; margin-top: -10px; margin-right: -10px; position: absolute; top: 0; right: 0; } .ml-error input, .ml-error textarea, .ml-error select { border-color: red!important; } .ml-error .custom-checkbox-radio-list { border: 1px solid red !important; border-radius: 4px; padding: 10px; } .ml-error .label-description, .ml-error .label-description p, .ml-error .label-description p a, .ml-error label:first-child { color: #ff0000 !important; } #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow.ml-error .label-description p, #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-checkboxRow.ml-error .label-description p:first-letter { color: #ff0000 !important; } @media only screen and (max-width: 400px){ .ml-form-embedWrapper.embedDefault, .ml-form-embedWrapper.embedPopup { width: 100%!important; } .ml-form-formContent.horozintalForm { float: left!important; } .ml-form-formContent.horozintalForm .ml-form-horizontalRow { height: auto!important; width: 100%!important; float: left!important; } .ml-form-formContent.horozintalForm .ml-form-horizontalRow .ml-input-horizontal { width: 100%!important; } .ml-form-formContent.horozintalForm .ml-form-horizontalRow .ml-input-horizontal > div { padding-right: 0px!important; padding-bottom: 10px; } .ml-form-formContent.horozintalForm .ml-button-horizontal { width: 100%!important; } .ml-form-formContent.horozintalForm .ml-button-horizontal.labelsOn { padding-top: 0px!important; } } .ml-mobileButton-horizontal { display: none; } #mlb2-14362251 .ml-mobileButton-horizontal button { background-color: #000000 !important; border-color: #000000 !important; border-style: solid !important; border-width: 1px !important; border-radius: 4px !important; box-shadow: none !important; color: #ffffff !important; cursor: pointer; font-family: ‘Lucida Sans Unicode’, ‘Lucida Grande’, sans-serif !important; font-size: 14px !important; font-weight: 700 !important; line-height: 20px !important; padding: 10px !important; width: 100% !important; } @media only screen and (max-width: 400px) { #mlb2-14362251.ml-form-embedContainer .ml-form-embedWrapper .ml-form-embedBody .ml-form-formContent.horozintalForm { padding: 0 0 10px 0 !important; } .ml-hide-horizontal { display: none !important; } .ml-form-formContent.horozintalForm .ml-button-horizontal { display: none!important; } .ml-mobileButton-horizontal { display: inline-block !important; margin-bottom: 20px;width:100%; } .ml-form-formContent.horozintalForm .ml-form-horizontalRow .ml-input-horizontal > div { padding-bottom: 0px !important; } } @media only screen and (max-width: 400px) { .ml-form-formContent.horozintalForm .ml-form-horizontalRow .horizontal-fields { margin-bottom: 10px !important; width: 100% !important; } }function ml_webform_success_14362251() { var $ = ml_jQuery || jQuery; $(‘.ml-subscribe-form-14362251 .row-success’).show(); $(‘.ml-subscribe-form-14362251 .row-form’).hide(); } fetch(“https://assets.mailerlite.com/jsonp/918262/forms/119753320103413631/takel”)

Leave a Reply