If you’ve ever scratched your head wondering how to update your site’s header once and have it magically reflect across every single page and post, you’re in good company. I’ve been down that rabbit hole too, wrestling with WordPress’s Block Editor, Site Editor, templates, and template parts. In this guide, I’ll walk you through everything—from the basics of Block vs. Site Editor to the nitty-gritty steps of creating a brand new header template part and applying it across your entire site. Plus, I’ll spill why simply creating a template part doesn’t auto-magically roll out everywhere (spoiler: it’s for flexibility!).

What you’ll get:

- A clear understanding of Block Editor vs. Site Editor

- Confirmation of when to use each editor

- The difference between global structure (styles) and templates

- A detailed, step-by-step walkthrough for changing or creating a header template part

- Answers to common questions, like why template parts aren’t automatically applied

- SEO-optimized headings and keywords to help search engines find this post

Let’s dive in!

1. Block Editor vs. Site Editor: Two Different Worlds

When I first started with Gutenberg, I thought, “This block thing is cool,” but I didn’t fully grasp the bigger picture. The magic of WordPress 5.8+ introduced not just the Block Editor but the Site Editor—and they serve different masters:

- Block Editor (a.k.a. Gutenberg)

- Scope: Individual posts and pages

- Use it for: Creating and editing content blocks like text, images, galleries, and embeds

- Example: Publishing a new blog post with rich media, formatting, and custom layouts

- Site Editor (Full Site Editing / FSE)

- Scope: Your entire website

- Use it for: Designing templates, template parts (header, footer), and global styles (fonts, colors)

- Example: Tweaking your header layout, changing the blog archive design, or customizing the footer across all pages

Why this matters: If you try to edit your header in the Block Editor, you’re only touching one page at a time. To change your site’s global header, you’ll need the Site Editor. Simple as that!

2. When to Use Block Editor vs. Site Editor

You asked: “If I want to change templates/patterns, use Site Editor; for changing individual posts/pages, use Block Editor. Correct?”

✅ Yes—that’s exactly right.

- Block Editor = Individual Content

- Think: I want to update my About page text, add an image gallery to this page.

- Site Editor = Global Structure + Templates

- Think: I want a new header, update my footer, change how all blog posts look.

Tip: Ask yourself, “Do I want this change on just this one page, or everywhere?”

3. Templates vs. Global Structure (Styles): Not the Same Thing

This one tripped me up more than once. Templates and global styles are siblings, but they play different roles:

| Feature | Templates | Global Structure (Styles) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Layout blueprints for page types | Site-wide design settings (fonts, colors, spacing) |

| Scope | Specific page types (single post, archive, page) | Entire site (all templates) |

| Edited in | Site Editor → Templates | Site Editor → Styles panel |

| Examples | Single Post layout, Archive layout | Button styles, Link colors, Typography |

- Templates: Imagine blueprints for each room in a house—kitchen blueprint, bedroom blueprint. If you renovate the kitchen blueprint, all kitchens look new.

- Global Structure: This is your interior design style—wall paint, baseboard trim, tile choices—applied everywhere.

Bottom line: When you edit a template, all pages using that template update. When you tweak a global style, fonts, colors, and spacing shift site-wide.

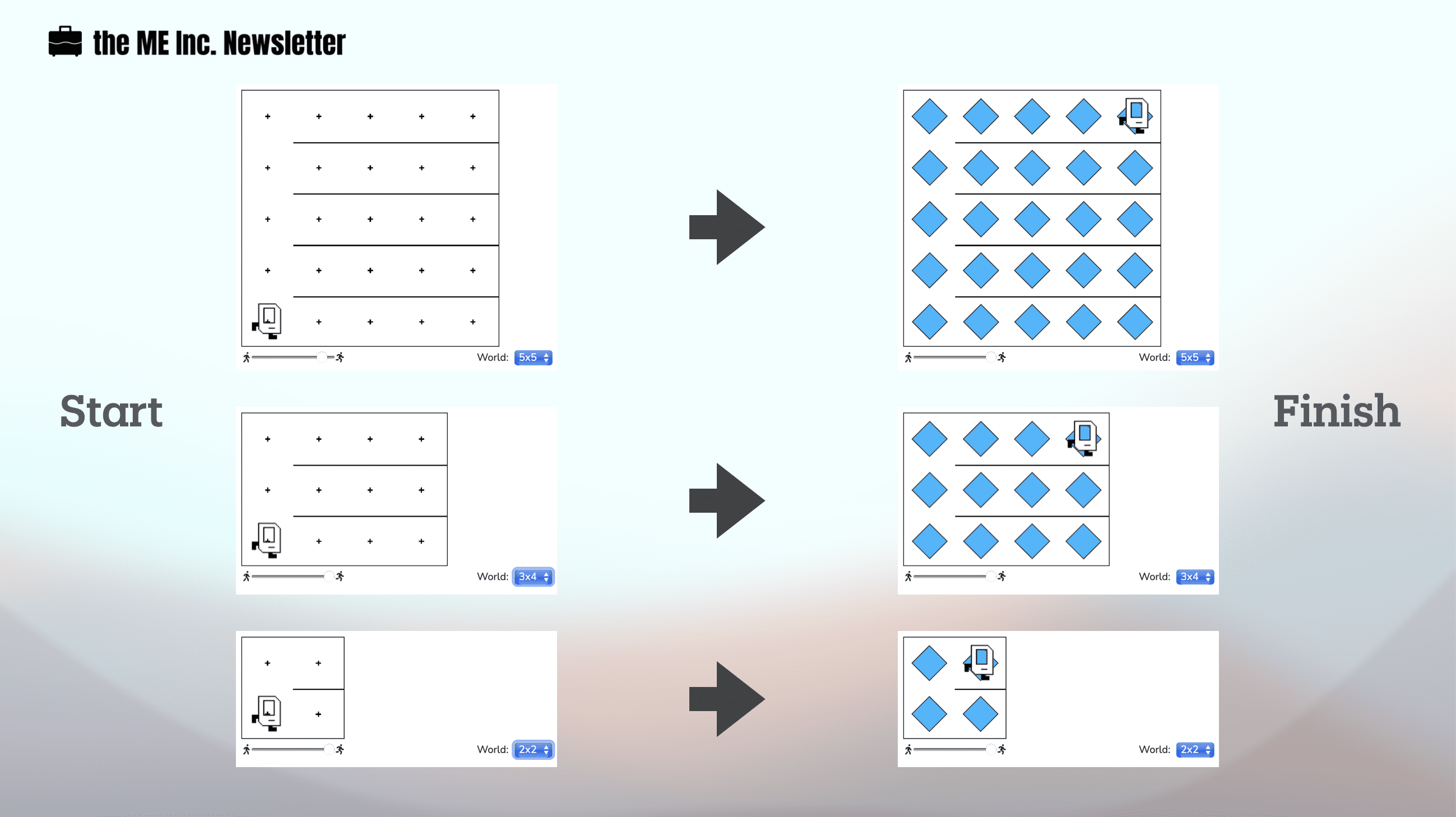

4. Step-by-Step: Changing the Header Site-Wide

Ready to create or change your header and have it show up on every page? Here’s the straightforward way:

- Open the Site Editor

- Go to Appearance → Editor in your WordPress dashboard.

- Create or Select a Header Template Part

- Click the WordPress logo (top-left) → Template Parts → Header.

- To create: Click Add New, name it (e.g., “Custom Header”), choose type Header, and click Create.

- To use existing: Select the header part you want.

- Design Your Header

- Use blocks: Site Logo, Navigation Menu, Buttons, Social Icons, Search.

- Adjust spacing, colors, typography in the block settings or Styles panel.

- Save Your Header Template Part

- Click Save. Your header part now exists, but it’s not yet applied to any templates.

- Apply the Header to Templates

- Still in the Site Editor, navigate to Templates (Single Post, Page, Archive, 404, Search, etc.).

- For each one:

- Click the template → select the old Header part → delete it.

- Add a block: Template Part, choose your new header.

- Click Save.

Pro Tip: If your theme uses the same header for all templates by default, you might only need to replace it once, and the change ripples across.

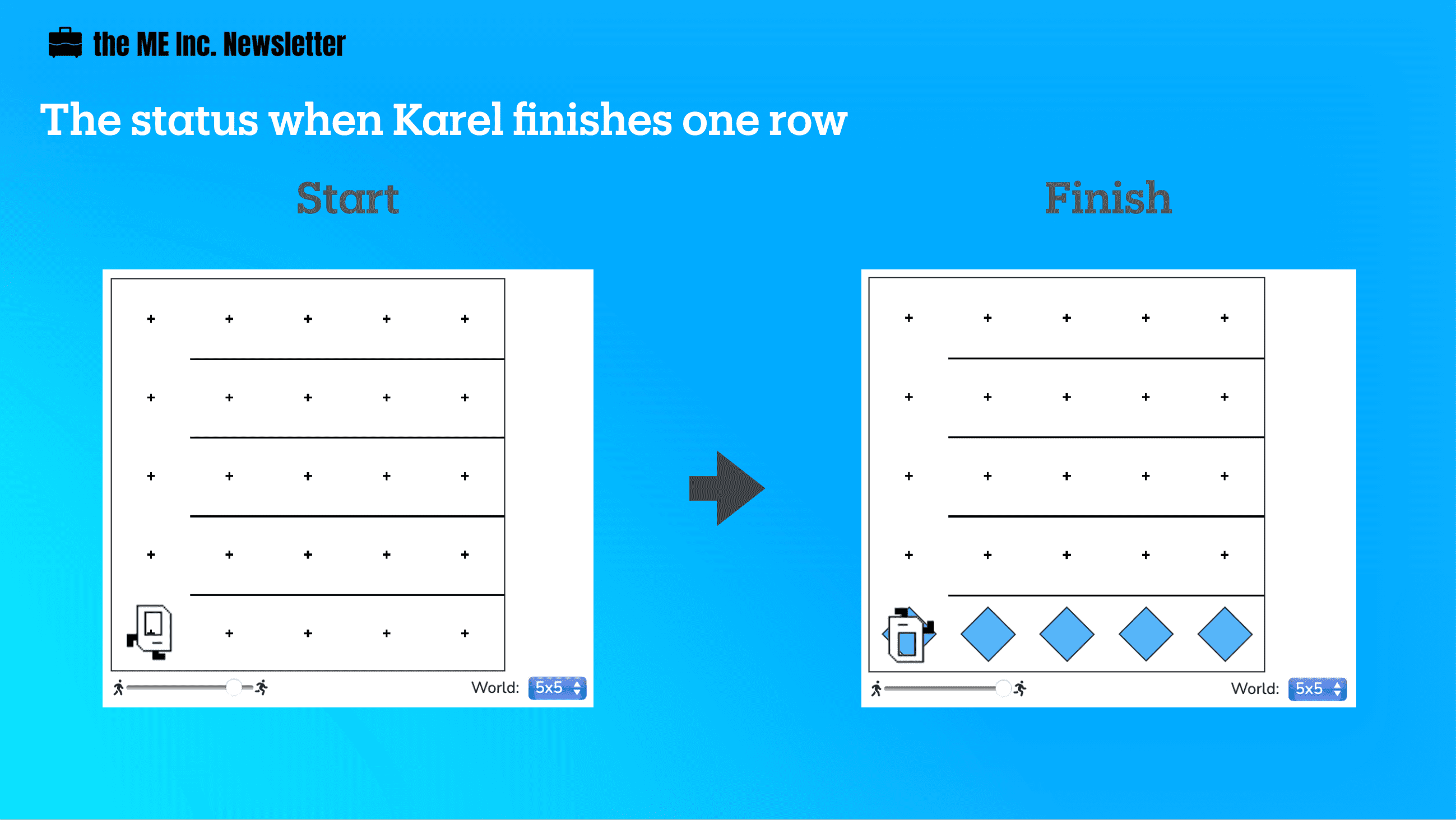

5. Why a New Template Part Doesn’t Auto-Apply

You might wonder: “Why doesn’t WordPress just swap in my new header everywhere?”

Here’s the thing:

- Flexibility Over Automation: WordPress lets each template decide which header it uses. That means you can have different headers: a minimal one for landing pages and a full one for blog posts.

- Manual Control: By creating template parts and assigning them manually, you get precise control over which templates use which parts.

It’s a bit more work up front, but it saves you from unintended changes down the road. Imagine if you updated your header for your blog but then accidentally lost the custom header on your sales page—that would be chaos!

Conclusion

Changing your WordPress header site-wide doesn’t have to feel like a treasure hunt. With the Site Editor, template parts, and a bit of manual swapping, you can design a beautiful header once and have it show up everywhere. Remember:

- Block Editor = posts & pages content.

- Site Editor = templates & global styles.

- Templates control layout.

- Global styles control appearance.

- Template parts are reusable blocks—but must be assigned to templates manually.